The MIT Climate Portal describes carbon offsets in this way:

Carbon offsets are tradable “rights” or certificates linked to activities that lower the amount of carbon dioxide (CO2) in the atmosphere. By buying these certificates, a person or group can fund projects that fight climate change, instead of taking actions to lower their own carbon emissions. In this way, the certificates “offset” the buyer’s CO2 emissions with an equal amount of CO2 reductions somewhere else.

Rochelle Toplensky writing for the WSJ’s Sustainable Business newsletter (Carbon Credits: Buyer Beware) finds that many carbon offsets fail to deliver on the promise of, um, offsetting carbon:

Planned paths to decarbonization vary, but many businesses plan to use carbon offsets. These tradable credits ostensibly represent emissions avoided somewhere else around the globe. But they remain controversial.

A Guardian investigation published Wednesday concluded that more than 90% of rainforest offset credits approved by one of the world’s leading voluntary registeries, Verra, don’t represent genuine carbon reductions.

Verra rejects the conclusions and says the newspaper’s analysis “massively miscalculates” its projects’ impact by not including project-specific deforestation risks when estimating what would have happened without the project.

Each side can make a coherent case but neither can conclusively prove what might have been. In the meantime, buyers of the Verra-approved rainforest credits—including BHP, easyJet, Gucci, Salesforce, Shell and the band Pearl Jam—are splashed across the media.

It is a stark example of the reputational risk that has some companies shying away from voluntary carbon offsets. The $2 billion market remains a bit of a Wild West, with a long list of investigations highlighting some projects that don’t do what they promise. The Wall Street Journal recently found most of the cash from a Peruvian project went to middlemen rather than the locals preserving the forest.

…

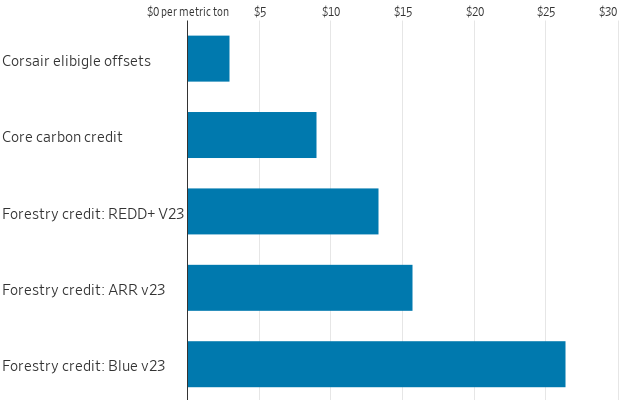

At best, companies will have a wide-ranging menu of “high-integrity” carbon offsets to choose from. Digging into the details of those offsets might be tough, although price can likely provide a hint about quality. After all, when choosing between a $5 seafood pasta and a $50 one, it is often obvious which one is more likely to give you food poisoning.

Here is the WSJ’s product quality guide based on price: