The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 boosted the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) budget over the coming decade by $79 billion, most of which is for increased enforcement. President Biden’s March budget includes the new spending and would more than triple enforcement outlays by 2031. House Republicans have proposed cutting the new IRS funding as part of the debt deal being negotiated.

At a Senate Finance Committee hearing last week, I argued that jacking up enforcement and auditing would cause collateral damage to the private sector. There are better ways to reduce taxpayer errors, including simplifying the code and overhauling IRS operations. Some analysts claim there is vast cheating by the wealthy and corporations, but the official IRS “tax gap” has not increased in decades relative to the size of the economy.

The IRS needs to audit at some level, but there is a balance. Higher audit rates would impose more costs on individuals and businesses in the form of time consumed, legal fees, anguish, and financial uncertainty. Another harm is that “audited firms are more likely to go out of business following the audit,” concluded one statistical study.

Policymakers should recognize that with such a complex tax code, it’s not just taxpayers who make mistakes. The IRS makes mistakes on calculations, sending notices, auditing, and other administrative and enforcement functions. In auditing, the IRS uses algorithms, discrepancies, and other factors to target returns. But the targeting gets more scattershot as audits increase, and so the collateral damage on taxpayers who have done nothing wrong rises rapidly as enforcement increases.

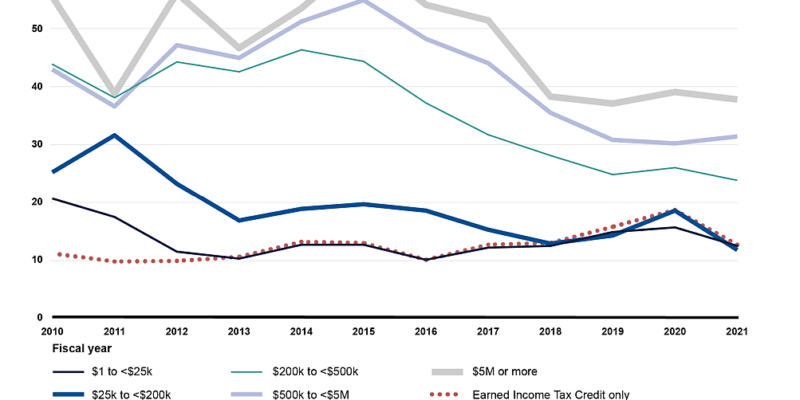

This effect is evident in the Government Accountability Office (GAO) chart below (from p. 13). At all income levels except the lowest, there were more IRS audits closed with no change in past years than today. That is partly or mainly because audit rates used to be higher, and the broader IRS dragnet encircled a larger share of taxpayers who had paid the correct amount. Today’s lower auditing rates may represent a better balance of costs and benefits.

By the way, note that higher‐income taxpayers have higher “no change” rates from IRS audits. They appear to make fewer errors and cheat less than lower‐income taxpayers.

A Congressional Budget Office (CBO) analysis of IRS enforcement finds, in parallel, that the marginal benefits to the government of enforcement falls as enforcement rises. The CBO estimated that adding $20 billion to enforcement would yield an additional $61 billion in tax revenues, but then adding a further $20 billion on top would yield just $42 billion in addition. These gains to the government should be considered alongside the costs of enforcement to the private sector and the general displacement of private activities as the government expands.

In sum, policymakers should remember that as audit rates rise, the share of taxpayers hit who are innocent increases, and also that the marginal revenue raised falls. A better way to boost compliance would be to improve IRS computer systems and taxpayer services, as promised in the agency’s strategic plan.

More on the IRS here, here, here, here, here, here, and here.

Data Note: The GAO says of the chart, “IRS officials explained that the no‐change rate has generally decreased because as IRS does fewer audits, it tends to select returns for audit that have the highest chance of resulting in changes.” Thus, the more auditing, the more time and energies are wasted in auditing returns that are already correct.