With this post I’m introducing a new gimic … a “Throwback: [insert day of the week]” post where we recycle content from the old days. The motivation is that [1] environmental problems haven’t gone away, [2] we provide the same solutions over and over again, [3] we’ve already said it and no one listened so why shouldn’t we say it again exactly like we did 10 years ago?

The other day, Tim scooped me on the water allocation crisis in the Western U.S. I was working on a post where I wanted to say something about an economic approach to water allocation: pricing. I wonder if the U.S. has made any progress on this issue since 2014.

Eduardo Porter:

Water is far too cheap across most American cities and towns. But what’s worse is the way the United States quenches the thirst of farmers, who account for 80 percent of the nation’s water consumption and for whom water costs virtually nothing.

Adding to the challenges are the obstacles placed in the way of water trading. “Markets are essential to ensuring that water, when it’s scarce, can go to the most valuable uses,” said Barton H. Thompson, an expert on environmental resources at Stanford Law School. Without them, “the allocation of water is certainly arbitrary.” …

The price of water going into Americans’ homes often does not even cover the cost of delivering it, let alone the depreciation of utilities’ infrastructure or their R&D. It certainly doesn’t account for other costs imposed by water use — on, say, fisheries or the environment — caused by taking water out of rivers or lakes.

Consumers have little incentive to conserve. Despite California’s distress, about half of the homes in the capital, Sacramento, still don’t have water meters, paying a flat fee no matter how much water they consume.

Some utilities do worse: charging decreasing rates the more water is consumed. Utilities, of course, have little incentive to discourage consumption: The more they did that the more their revenues would decline. …

While this may seem a mess, it is nothing compared to the incentives facing American farms. …

Their water rights are primarily subject to state law. In the West, they have been allocated by a method that closely resembles “first come first served.” The first farm that drew water had a right to whatever it needed pretty much forever. Junior users — who arrived later — had to stand in line.

Farmers pay if the government brings the water to the farm, say via an aqueduct from the Colorado River. But the fees are minimal. Farmers in California’s Imperial Irrigation District pay $20 per acre-foot, less than a tenth of what it can cost in San Diego. And the government has often subsidized farmers via things like interest-free loans to cover upfront investments. …

This is hardly the only obstacle to conservation. A farm that doesn’t use its full allotment of water risks forfeiting it for not putting it to “beneficial use.” And any water saved automatically flows to other farmers with junior rights. …

Spurred by the sense of crisis, incipient water markets show great promise. Santa Fe, N.M., has required builders to have water rights with their building applications since 2005 — giving farmers an opportunity to sell their rights to developers rather than using them for low-value crops.

In 2003, the San Diego Water Authority cut a deal with the Imperial Irrigation District — a large area of parched farmland near California’s Arizona border — to provide the city with 200,000 acre-feet of water at a price starting at $258 per acre-foot.

Seven states in the Colorado River system are starting a pilot program to explore a market between farmers and urban water authorities to help maintain water volumes in Lake Powell and Lake Mead.

This isn’t quite charging farmers for the water they use. But that may be a bridge too far, considering the tight margins of many farms and the political clout of many farmers.

Still, markets such as those timidly emerging in the West could not only free water for the users who value it more, but they could also provide farmers with the revenue needed to invest in water management technology.

via www.nytimes.com

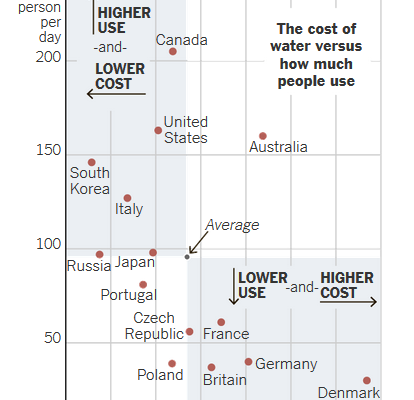

I like the graphic: